In 2000 journalist Ritu Sehgal witnessed a modern miracle in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. This is how she set the scene: "It is a sleepy Sunday afternoon in Makkanpur, Old men sit in front of

the village shop in the shadow of the Neem tree playing cards and drinking tea. Suddenly they raise their heads. Two unusual guests approach.... Clad in saffron robes, a sadhu comes nearer, followed by his disciple. Barefoot through the mud the holy man and his companion move with measured steps. The sadhu lifts his hand for a blessing and enters the premises of the sarpanch's (village head's) house. Some young men run and bring a charpoi (traditional bed) and place it in the middle of the courtyard. The holy man sits and folds his legs ceremoniously. Eyes fixed in the clear blue afternoon sky, he does not move. The news of the sadhu's arrival spreads fast.... Within minutes the whole village is present. All eyes are fixed on the holy man. The sadhu rises. Through his disciple he lets the villagers know that a curse is lying on Makkanpur. He makes them see the bad omen with their own eyes. He throws a coconut on the stony ground: it breaks, blood squirting out and splashing all around. The audience is awestruck. He has come here, the sadhu lets them know, to use his magical powers to free them from threatening disaster and misfortune."

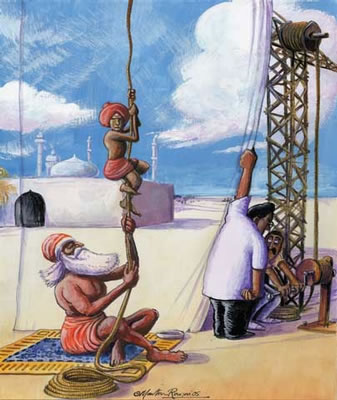

What follows is an extraordinary display of those supernatural power: the holy man causes a pot to burst into flame and produces eleven lemons from his mouth. He pierces his cheek without drawing blood, reclines on a bed of nails, and appears to levitate under a sheet. The crowd are enraptured. Having proven his power he can now be relied on to cure the town of its curse.

It's all too easy to be seduced by this portrait of the mystical East, to assume that its rich spiritual heritage brings a meaning and beauty to life so lacking in the materialist, sceptical west. Attracted by the notion of gurus, sadhus, babas and tan-tricks roaming the land, selflessly curing the masses of affliction, politicians and film stars flock to receive blessings from super-gurus like Sri Sathya Sai Baba.

But on this occasion,

the village witnesses a rather different kind of miracle. Just as the performance is reaching its climax, with the sadhu hovering above the ground, a man leaps up from the crowd and shouts "Stop! This is no holy man". He tears down the sheet under which the guru is 'flying', to reveal the two hockey sticks he is using to raise it.

"We are rationalists" declares the intruder, Sanal Edamaruku, secretary general of the Indian Rationalist Association. "We have come here to show you how sadhus and god-men are using simple tricks to cheat you." The sadhu himself is divested of wig and beard and revealed as a completely ungodly rationalist volunteer. He's no guru – just very skilled at conjuring, and well-schooled in the basic chemistry which dictates that certain fluids will ignite on contact, that lit camphor won't burn the skin, that weight evenly distributed on nails won't puncture. The miracle is that the spell has been broken. Once the crowd have absorbed the shock, and broken into laughter, this poor, remote village has been liberated from superstition. Perhaps for ever. As Edamaruku says "what may look like Sunday

entertainment for children, is in fact nothing less than breaking the little hook on which the god-men's enormous power, and the fate of their victims, hangs."

Despite a tenacious western orientalism which overemphasises and overvalues Indian religiosity, reinforced by the homegrown 'Hindutva' movement propagated by the BJP, India has a long and distinguished rationalist tradition which is considerably older than that of the west. According to Nobel prize-winning economist Amartya Sen, the seeds of rationalism were planted many thousands of years before the Enlightenment, and centuries before Jesus Christ.

Buddha himself, or at least Siddharta (who may or may not have been the first

Buddha), could lay claim to being the first rationalist, and even the Hindu sacred text the Ramayana contains the character of Javali who advises the god-king Ram that "there is no after-world, nor any religious practice for attaining that…[religious] injunction have been laid down in the [scriptures] by clever people just to rule over [other] people." This tradition also includes practical political rationalism such as that of Buddhist Emporer Ashoka (273 - 232 BC) who declared religious tolerance and equal human rights with the aim of unifying all India.

Contemporary groups like Edamaruku's Delhi-based Indian Rationalist Association (IRA) and the Satya Shodhak Sabha (Society of Truth Seekers) based in Gujarat, are direct descendents of this tradition. More immediately, they build on the work of the founding fathers of modern Indian rationalism: Mahatma Phule (1827-1890), Periyar Ramasami (1879-1973) and Gora (1902-1975).

Phule, son of a vegetable vendor and educated through the philanthropy of family friends, was one of India's most influential social reformers, campaigning against the caste system, the subordination of woman and the invested power of the Brahmin. Periyar, the '

Voltaire of South India', was born in Tamil Nadu to an affluent religious family and made his name publicly challenging religionists. Drawing inspiration from the French revolution, he loudly and publicly attacked religion as superstition and exploitation. He was a powerful orator and fearless critic: "It gives me extraordinary pleasure", he wrote, "to fling at the pundits their own contradictions, and thus perplex them."

Gora was a high caste Hindu who became a global symbol for 'positive atheism' as well as a tireless campaigner for human rights, and alongside Gandhi, a protester against colonial rule and godfather of democratic India. Phule, Periyar and Gora can be credited with taking the principles of Indian scepticism, rationalism and humanism to a mass audience, though they rarely appear on western lists of rationalist heroes.

Building on this pioneering work it was the Sri Lankan based rationalist Abraham Kovoor (1898-1978), who innovated and extended the techniques of miracle exposure. Kovoor, the son of a vicar, was a professor of Botany, but it was after retirement that he really made his mark as a campaigner against god-men and supernatural fraud. He travelled widely and wrote copiously, bringing all his scientific training and rhetorical power to bear on the practices of the shaman and supposed magicians. He undertook four 'miracle exposure' tours of India in the early 1970s, organised by the IRA and Sanal's father Joseph Edamaruku, even visiting the ashram of Sai Baba, one of Indian's most prominent and popular holy men who, despite his claims to be a god on earth, was unwilling to meet the professor to prove his supernatural powers.

After Kovoor's death in 1978 his mantle was taken up by Basava Premanand (born 1930). Premanand, probably the most box-office of the miracle exposers, actually started out as a disciple of Sai Baba. Becoming disillusioned in 1975 (having transferred a lot of his property to the guru), and inspired by Kavoor, he devoted himself to exposing Baba's use of (pretty amateurish) prestidigitation to produce 'holy ash' and the cheap trinkets with which he wows his large, and far from exclusively Indian, gaggle of devotees.

It was Kovoor's visit to Gujarat in 1976 which inspired a group of rationalists there to form Satya Shodhal Sabha (SSS), named after Mahatma Phule's original 1870s organisation. Kavoor's demonstrations convinced a new generation of activists – composed, like most of India's activist-rationalists, of volunteers from the ranks of education and academia spiced with disillusioned former-converts – that public demonstrations and exposures were the most effective way of educating the public and undermining the credibility and the power of exploitative faith healers, sadhu and the rag

tagholy men who tour the country exploiting ignorance and fear where they find it. Exposures are part of a sophisticated strategy to influence popular opinion against supernaturalism.

"We do not go out and talk about whether God exists or not, or get involved in abstract disputes of that nature," says Professor BD Desai, secretary of the SSS, who have performed over 1500 miracle exposures since 1982. "We are not concerned with showing how clever we are compared to the ignorant masses. We want to talk to people in a language they understand, to expose falsehood and contradictions, and show how the miracles are basically a ploy to distract and misguide people from their genuine problems."

The SSS work on a number of fronts simultaneously. In addition to exposing the fakery of fakirs, they work as a semi-official abuse monitoring service, helping to identify, expose and prosecute sadhus involved in sexual exploitation. "In India male children are highly valued. If a woman cannot conceive a male she will often seek out the help of a sadhu, who claims that using ritual and sacrifice he can heal her. Often such situations end up in rape or sexual abuse. A complaint will be made to us, we will send undercover volunteers to investigate and gather evidence, and if possible go to court to help secure a conviction." In this they are fully supported by the local police and receive a degree of state support.

Then there are the cases of supernaturalism which do not involve shifty sadhus, but more complex and fascinating psychological motives than mere greed. Professor Desai relates the story of a 14 year-old boy in the remote sea side village of Kantiyazad, who was believed to have been possessed by the avatar (spirit) of the god Jalaram Bapa – how else to explain the fact that he had begun intoning verse in Sanskrit, a language he did not know? When rationalist investigators arrived they discovered that the boy, neglected in favour of two

smart older brothers, had memorised the verses, which were pasted up in his father's shrine. The apparent possession was an attempt to gain the attention and approval of his father. Or how about the strange appearance of cuts in a young wife's sari every time she was due to leave the house with her husband? On closer inspection, the evil omen turned out to be the result of some nifty scissor work by a frustrated sister-in-law confined to the house. In both cases the investigators made a point not to expose the fraudsters in public, but to work with the families to achieve some kind of settlement which would remove the motive for the false possession.

Each case reveals the deep connection between India's structural inequality – the caste system, gender subordination – and the lure of supernaturalism, the desire to be heard, to escape or to grasp some approximation of meaning apparently offered by the holy-rollers. The crucial skill of the Indian rationalist tacticians is to be able to combine a sense of theatre comparable to that of the most extravagant sadhu, with a recognition of the link between India's social inequalities and superstition. Desire for social transformation, in the west more associated with radical

progressive politics, goes hand in hand with the desire to expose fraud. Tactically astute, organisations like the SSS know that miracle exposures, successful as they are, will not of themselves transform Indian social inequality, but they form the conspicuous surface of an underlying strategy: "We are wedded to social change, but to create acceptability we need to make inroads in the thinking of the people. Exposures achieve this, as does our voluntary work of all kinds. We have exposed over 50 frauds, and many mid-level gurus have left

the state, but our focus is on the people. First and last we want people to think rationally. Once that happens the gurus will not remain anywhere."

Professor Desai is clear that while the forms of Indian activism can be an inspiration for a renewed practical western rationalist project, western traditions of rationalist and humanist thought remain an essential model for India: "Our entire enlightenment depends on the west, and we have a lot more to learn." In his speech at the conference in 1999 which celebrated 100 years of the Rationalist Press Association (RPA), Sanal Edamaruku was explicit about the vital role played by the availability of cheap copies of classic western humanist texts, printed by the RPA, publishers of the journal you are reading now: "The Cheap Reprints and the Thinkers' Library series during the middle of the 20th century reached far-off places and provoked thinking people to come out and plan organised efforts to influence change." One of the most influential successes of Indian atheist publishers was to translate much of the Thinker's Library, and many other classics of humanism, into local languages like Malayalam. "If you happen to come to Kerala one day," Edamaruku concludes "don't be too astonished to meet a teashop boy who has read Charles Darwin's Origin of Species." The influence, in the end, is two-way.

Indian rationalism continues to claim some significant victories: exposing not only dozens of home-grown charlatans but also imported varieties such as evangelical fraudster Morris Cerullo and faith healing huckster Clive Harris; ensuring that astrology was deprived of the status as a legitimate profession and preventing it from being adopted on the university curriculum; and securing the right to register 'no caste or religion' on official forms, are just some of the practical achievements they can claim. But neither Desai nor Edamaruku are complacent about the challenges still to come. To the problems of illiteracy, superstition and sectarianism are added the renewed perils of Islamic fundamentalism and the machinations of imported Christian missionaries.

For the rationalists, the work goes on. Professor Desai, since retirement working harder than ever for the cause, continues to lecture, speak and write (his organisation has published scores of books and pamphlets in Gujarati) as well as appearing as a material witness in abuse cases. Edamaruku runs the IRA with tireless enthusiasm, using all media – TV, the Internet, magazines, public speaking – to get the message out. From exposing 'the prime minister's astrologer' Lachman Das Madan on live TV to running his paranormal investigation centre which exposes contemporary hoaxes such as the photograph of the

giant skeleton, reputed to be a Rakshasa (mythical

giant), in fact revealed as a fairly clumsy piece of photo trickery, Sanal Edamaruku is probably the hardest working man in the miracle-busting business. His most recent success was on live television across the subcontinent. On October 20th Indians were glued to their TVs watching live as Astrologist Punjilal, who had predicted that he would die between 3 and 4pm on that day, lay down to his fate. Edamaruku had appeared on the 10 o'clock news the night before, confidently predicting that nothing would happen. By the time the astrologist gingerly arose at five past four, and was declared in perfect health by a doctor, Edamaruku had struck another, very public, blow to the credibility of supernaturalism (

a feat he repeated with even more drama in 2008).

These activists and many others with the same dedication to truth and ability to capture the imagination of the crowd, offer perhaps the best example of how rationalism can be both profound and entertaining. Perhaps, if they have time, some of these practical rationalists might find time to come over to Britain and help us with our superstition issues.

(New Humanist Volume 120 Issue 6 November/December 2005)